The rides succeeding the first Frank Lloyd Wright tour took us to some of the most important locations of modern architecture in Los Angeles. Visiting R.M Schindler's bohemian campsite in West Hollywood, Leonard Malin's Chemosphere in the Hollywood Hills, and George Sturges' cantilevered Usonian in Brentwood was a pleasure to say the least. Stunning works that helped define the concept of 'California Modern', questioned our notion of how a building engages its site, and what 'American' architecture is, and consequently has the opportunity to be. The homes were awesome. The rides, though, are where formality is forgotten, and the bickering begins.

The rides were awful. Well, at least they hurt. A lot. And that we're not going to debate. And that's the point.

Covering the final works of Frank Lloyd Wright took us from Silver Lake all the way to Rodeo Drive (I know, I would never have expected to see Wright on Rodeo, but hes there, trust me), and eventually over to Brentwood to visit said Usonian wonder. It was doable ride except for a quick climb up to visit Lautner's Wolff Residence perched above the Sunset Strip. Most of the stops were relatively low lying and not too far off the beaten path. That is, unless you make a wrong turn and find yourself in a bamboo grove staring eye to eye with something that looks like a cross between Stonehenge and a shoji temple. A shoji templed which Schindler himself used to live in.

Everything is hand crafted. Everything. Site cast concrete formed by burlap give the tapered walls that enclose the main living spaces a texture that is like a fluid in suspended animation. The timber framing that fills out the remaining elevations dances along the house like a ribbon whipping in the wind. Each vertical break in the strand defines both itself and an opportunity to continue the logic of the form along another plane; a plane which opens to the courtyard like a tent that opens to a campsite. There's even a hammock, except in this case, it's in the trees, not hanging between the base of two of them. Vacated of all furniture and personal belongings, the house remains merely a shell, but in so being, it becomes more than a series of well composed architectural elements. The Schindler House in its present form represents the strength and power of the diagram in how it can inform architecture. Stunning.

Skip ahead another ten miles; the odometer clicks 20, and you're looking forward to one brief stop before returning to the east side, there's one last climb. 'One last climb'. Ha. Don't believe it when you hear it. That last stretch up into the Brentwood hills to see the only Usonian house in Los Angeles is a rough one. Your legs will be jelly. You will be out of breath. And, at the time, you will hate having agreed to doing this. But when you get to the top of Skyeway Road, and you're hallucinating from the lack of oxygen, its all worth it. And that's the point.

Wright's house for George Sturges is Los Angeles' only Usonian home. And it fits the bill nicely. Typical to the Usonian parti, the house makes use of native elements like redwood and brick, utilizes verandas and generous overhangs to take in views while making use of passive cooling strategies, and maintains a relatively modest footprint. The most unique aspect about this Usonian in particular, though, is the way it approaches the site (not a big surprise given that Lautner was the associate in charge of the design at the time). The house seems to be a ship cresting over the top of a twenty foot wave, only its hull is is a frighteningly cantilevered patio sitting above a brick faced retaining wall which seems to slice through the home as it forms the chimney above. The view from the patio is amazing though. On a clear winter's day, all of LA, whitecaps in the background to boot, is visible. Its at this point that the climb, the pain, and the slight disorientation is well worth it. Leave the bickering for later, this is about as good as it gets. Well, almost.

The next ride we collectively termed 'Broken Legs, Hot Homes' for a reason, and its not one that needs a lengthy explanation.

Los Angeles is a city intimately linked to its topography. Some of the best spaces and structures can only be found after you find yourself at the end of a steep ascent, or the bottom of a canyon road looking out into the Pacific. Unfortunately, the best architecture seems to be included in the former. Strictly. 'Broken Legs' took us up to Mulholland to visit a study of the minimalist case in Pierre Koenig's Bailey House, a tree house for Ellen Jansen (and R.M Schindler, but don't tell anyone you know), and Lautner's masterpiece floating up in the clouds above the San Fernando Valley.

These homes are astonishing. Just like the last ride. After the uphill battle is over, there's only 'one last climb'. Just like the last ride. And the ride is awful...but way worse than the last ride.

The ride by the crow's wings is no more than 10 miles 'a to b', but it just never seems to stop going up. The first stop at Schindler's Jansen Residence, is, in theory, 90% of the climb, seated essentially at the foot of Mulholland Drive, but the climb to Koenig's Bailey House makes that 10% seem pretty significant. Thankfully, though, the simplicity of the Bailey House can smooth over any anxious tendencies with just a few strokes of the brush. Situated atop a pristine and uncharacteristically level site, the house, with a modest square footage of not much more than 1000sf, is one of Koenig's earlier examples of what has come to define California Mid-Century Modern. Clean crisp lines, large expanses of glass with views to the horizon, and attention to even the most minute detail.

Before our final stop, we take a detour to visit a Lautner masterpiece with an unexpectedly unfriendly owner, and then its off to a house that is both 'of heaven and earth' and neither at the same time. Oh yeah, and one more climb. I swear.

Lautner's Chemosphere is that 'almost'. Perched above Mulholland Drive and overlooking the entire San Fernando Valley, the Chemosphere is the ultimate examples of architecture's attempt to reconcile its impact on the earth. A veritable flying saucer hovering over what had, at one point, been deemed and unbuildable slope, the house is modest octagonal single story residence resting on top of a single concrete column. Views every which way, and approachable only by a sky bridge, which is, in turn, only approachable by a funicular. There really is nothing like it. Not even close. So theres only one thing to do. Throw caution to Benedikt Taschen's wind, and climb the slope to look over what Chemosphere looks over. The view is amazing, but the most interesting thing about being up close and personal with the house and the views that it affords is the relationship that you then form with it. Viewed from below, the house reads mostly from its underbelly (and one whose texture is actually kind of similar to the texture of Sturges' wood fascia cantilever), but from above the house takes on a completely different personality. The glazing on each of sides of the octagon are split by the laminar beams supporting the roof which give them the appearance of being more like eyes on one of the house's many faces. So you sit and stare. And Chemosphere stares back. You nod in a kind of quiet appreciation to what Chemosphere has let you see and be a part of. Then you lay back against the hillside and gaze off into the distance, and that ride up that had you swearing to the heavens leaves you there, without a care in the world. And thats the point.

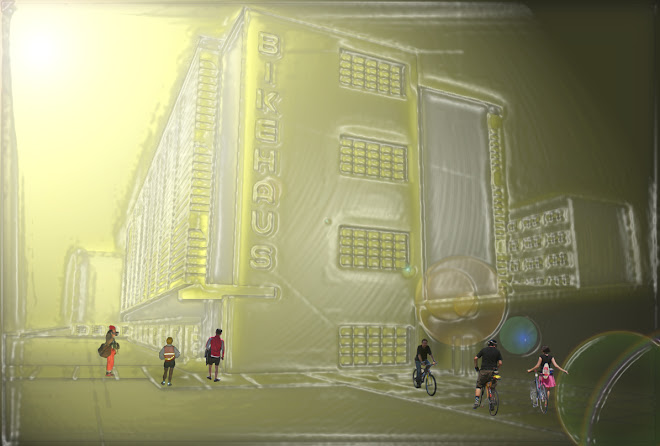

BikeHaus seeks to open a dialogue generated by an appreciation for great design, a sensitivity to our surroundings, and a willingness to share out own thoughts and feelings by engaging the wonders of modern architecture in Los Angeles one ride at a time. The rides are rarely a breeze. To a degree this is unavoidable. Los Angeles is hilly. But, it is also intentional. Theres nothing quite like gasping for air and cringing with each new step, only to look up and be completely blown away. We love great architecture, but why not use it as an excuse to go for a good ride?

No comments:

Post a Comment